Slits and a Skull in ‘True North’, Galeria Fermay, Palma de Mallorca (2023)

Slits and a Skull in “True North”, Galeria Fermay, Palma de Mallorca (2023)

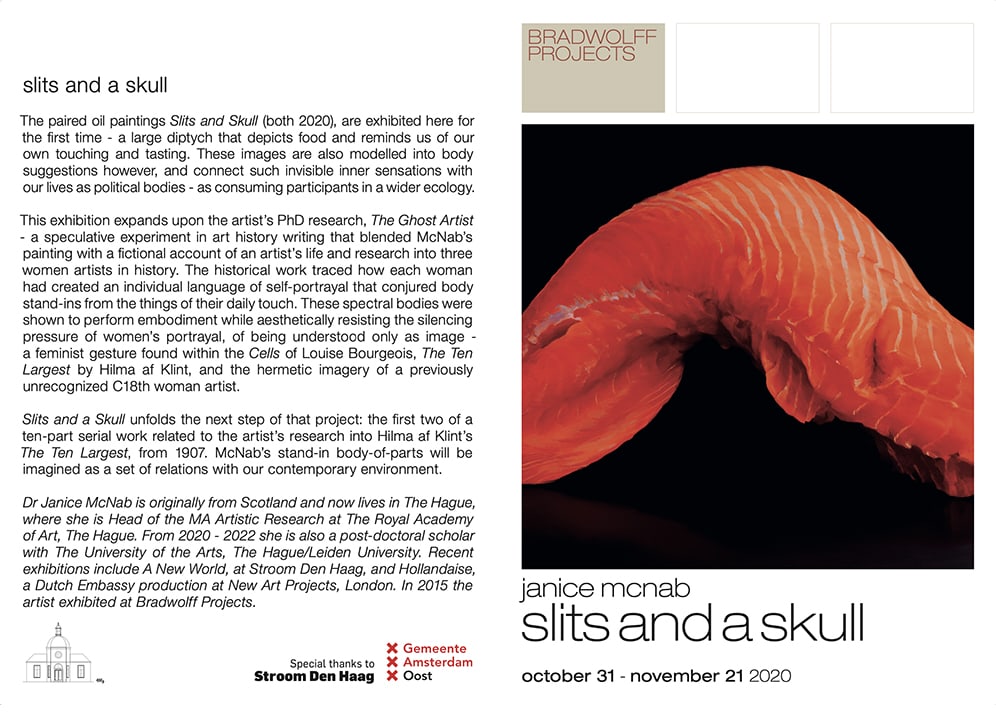

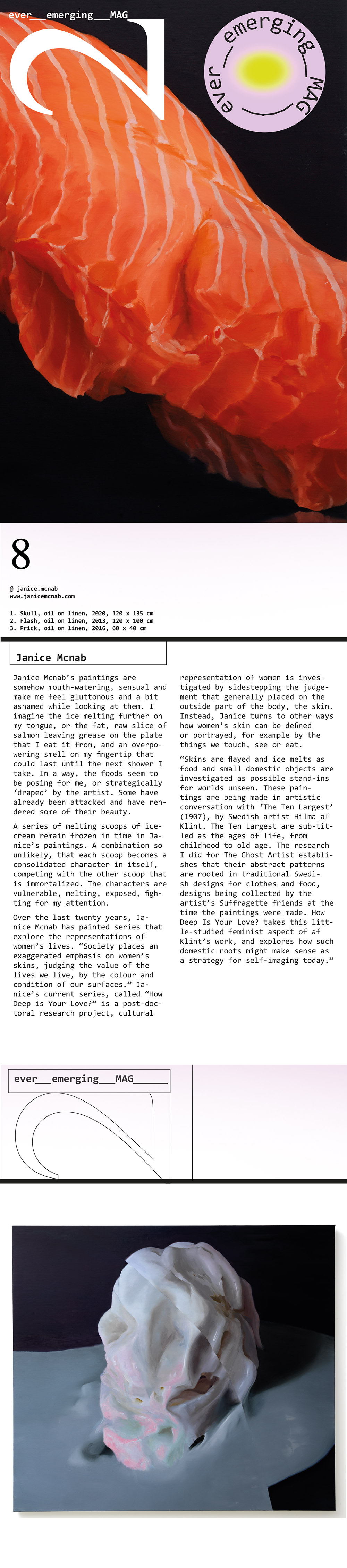

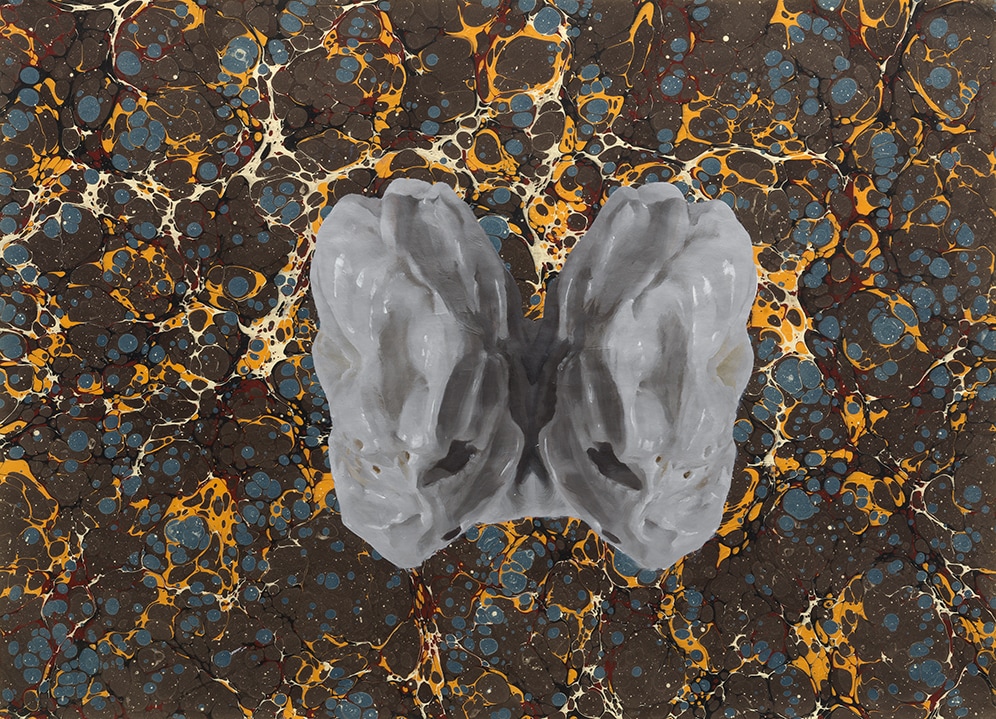

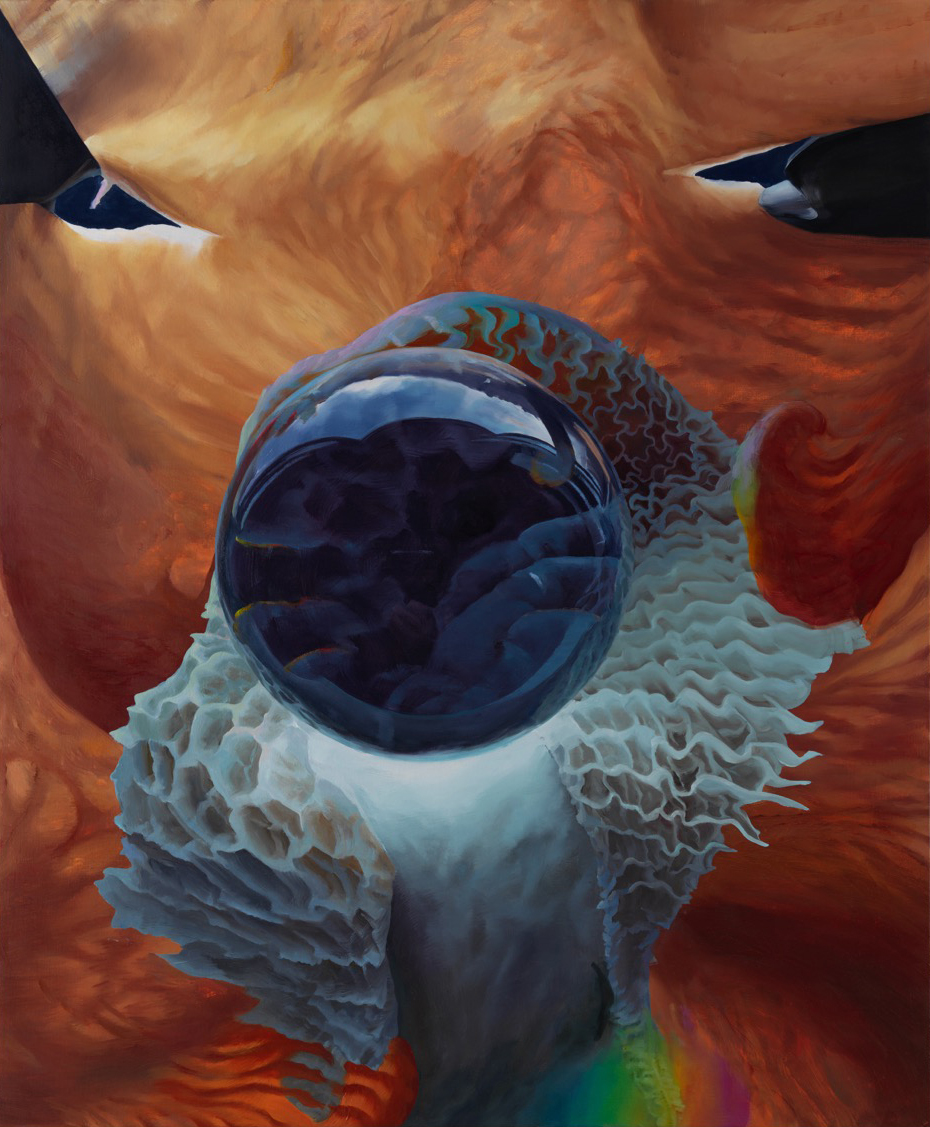

During the Covid-19 pandemic, McNab created a small group of paintings that responded directly to the isolation and fear the pandemic produced. In the main diptych, Janice McNab: Slits and a Skull, a figure is drawn from the skinned and slit body of a Scottish salmon, and a skull seen in a blob of ice cream — its image slit as if seen in a broken mirror. In Visibility, eyes are torn open with duct tape, while a doubled face / body, modelled from the stomach lining of a cow, supports a crystal ball. Food had a heightened resonance during the pandemic, its sensual pleasures gaining in value at the same time as supply lines faltered. It is a substance that goes both in and out of us, and here it is isolated and manipulated and asked to carry a sense of our deepest impulses, those towards sex and death.

Photo credits: Grimalt de Blanch and Galeria Fermay, 2023.

Elke Krasny responds to Slits and a Skull (2020)

Feeding ecological

empathy

Summer 2020. A studio visit has become a rare treat in pandemic times, and I cherish the invitation to Janice McNab’s workplace in The Hague. This is where I first see Slits and Skull, and since the encounter I have found myself in dialogue with the two paintings. Looking at the ice cream and the salmon I first thought of childhood food memories. Ice cream was an exception, bought as a cone at the ice cream parlor and enjoyed there, never at home, and living in a landlocked country, I don’t even remember when I first had salmon. I don’t think it was as a child. But today, when I open my freezer, there they are, the ice cream and the salmon frozen next to each other. Globalized food production has shaped my eating habits.

Looking at Slits and Skull had made me acutely aware of my own touching and tasting, but the isolated bodies depicted in these paintings also suggested my alienation from the environment my food comes from. A lack of context that passes into alienation from my own body as I eat. Mulling this over as I thought about the paintings, I grew certain that this was not just me, but that these works touched on something cultural and historical. The virus of 2020 has everyone thinking and feeling and caring about bodies differently, and I have started having long conversations with myself about globalized intimacies and intimate globalization.

How can it be that we feel detached from our food? We humans know that we are what we eat, but do we eat as if we understood the implications of this knowledge? Do we eat as if we knew that we are feeding on hyper- industrialized nature and a destroyed environment? Food is essential to life and among our most intimate encounters with ourselves. Entering our mouths, food passes over the pharynx and down the oesophagus, through the stomach and out. The environment has to enter into our bodies for us to stay alive. We feed on it, we are what we eat, so we also are the environment. What to make then, of the powerful legacies of modern Western thought that do everything to ensure we believe ourselves separate from it, that we believe nature to be separate from our culture? As feminist multispecies thinker Donna Haraway has pointed out, this is one of the “inherited dualisms that run deep in Western cultures.” The nature/culture divide has provided much of the intellectual legitimization for extractive, exploitative, and exhaustive capitalism, and the historical separation of mind from body, and culture from nature, privileges mind and culture in ways that are harmful to bodies and nature. Separating minds from the bodies they also are, separating humans from the environment they also are, has had violent consequences, and food has become caught in the split. These paintings were created as the pandemic has unfolded, and let us know more clearly than ever that we are what we eat, but have we learned to feel that we eat what we also are? Looking at McNab’s paintings, I keep asking myself how to unlearn detachment, and to learn differently from this violent legacy, to feel how intimately globalization enters our bodies with every bite we take.

The artist’s re-activation of the still life tradition invites us to re-think and re-feel these narratives. The stilled bodies of Slits and a Skull re-visit the ‘embarrassment of riches’ centrally displayed in historical still life paintings, but they return to the genre today to remind us of our continued entanglement in this economy, while also suggesting how culture might feed more ecological empathy. These paintings bear witness to our consuming relationship with the world, but they also contribute to our critical consciousness of this, as their beauty helps train our intellectual and emotional muscles to better understand ourselves as flows within our surrounding ecologies.

Prof. Dr. Elke Krasny is a cultural theorist and curator. She is professor of Art and Education at The Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. Her scholarship focusses on care in relation to emancipatory practices within art, architecture and urbanism.